What is required to fully decipher the contents of the black box mentioned above?

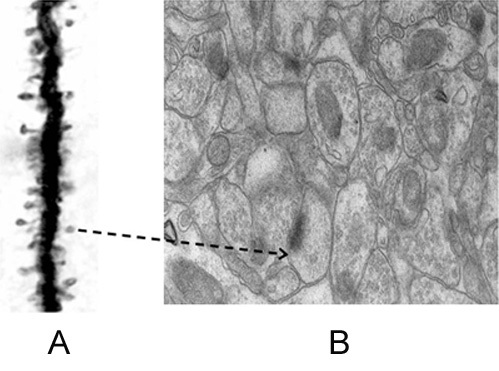

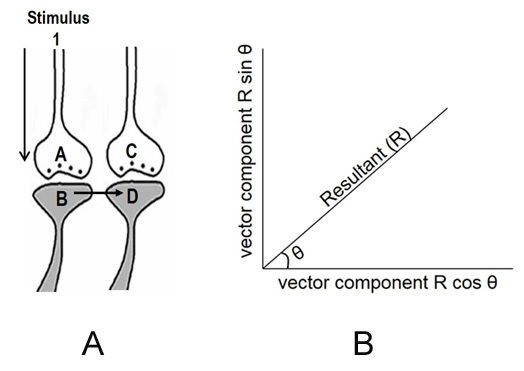

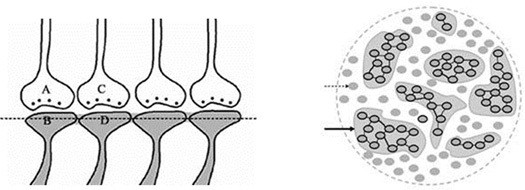

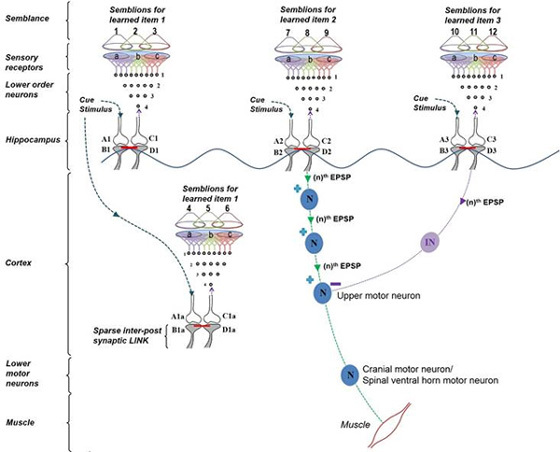

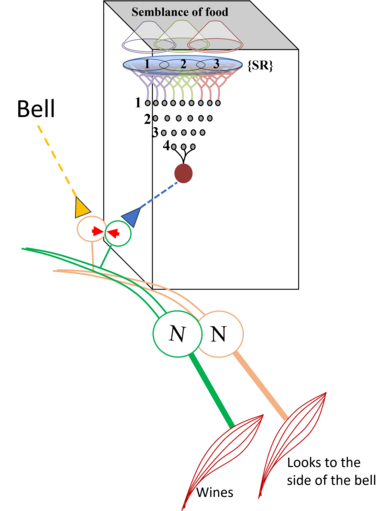

Further resolution of the dendritic spine structure is necessary, and this should be achieved without compromising the integrity of the surrounding extracellular matrix. Preserving this volume is crucial for identifying the formation and reversal of the most common inter-postsynaptic functional links (IPLs), which are thought to underlie working memory (see Fig. 12B). To fully understand the derived first principles and the algorithm responsible for integrating units of internal sensations, collaboration with foundational scientific disciplines – including physics, mathematics, computer science, and electronic engineering – is essential.

How does the artificial intelligence community currently view first-person properties?

Members of the AI community have begun to question how neuroscientists approach the task of providing a mechanistic explanation for cognition. They are eager for neuroscience to uncover the specific mechanisms by which the brain generates its functions. For example, see the article "Neurotechnology is Critical for AI Alignment" (cvitkovic.net), which highlights this growing interest.

References

Abbas AK, Villers A, Ris L (2015) Temporal phases of long-term potentiation (LTP): myth or fact? Rev. Neurosci. 26(5):507-546. PubMed

Abbott LF (2008) Theoretical neuroscience rising. Neuron 60(3):489-495. PubMed

Ahmad M, Polepalli JS, Goswami D, Yang X, Kaeser-Woo YJ, Südhof TC, Malenka RC (2012) Postsynaptic complexin controls AMPA receptor exocytosis during LTP. Neuron 73, 260–267. PubMed

Akerman S, Goadsby PJ (2005) Topiramate inhibits cortical spreading depression in rat and cat: impact in migraine aura. Neuroreport. 16(12):1383–1387. PubMed

Amaral DG, Dent JA (1981) Development of the mossy fibers of the dentate gyrus: I. A light and electron microscopic study of the mossy fibers and their expansions. J Comp Neurol. 195:51-86. PubMed

Antic SD, Zhou WL, Moore AR, Short SM, Ikonomu KD (2010) The decade of the dendritic NMDA spike. J Neurosci Res 88:2991–3001. PubMed

Ayata C, Lauritzen M (2015) Spreading Depression, Spreading Depolarizations, and the Cerebral Vasculature. Physiol Rev. 95(3):953–993. Article

Bányai M, Lazar A, Klein L, Klon-Lipok J, Stippinger M, Singer W et al. Stimulus complexity shapes response correlations in primary visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2019; 116(7): 2723–2732. PubMed

Beauchamp MS, Sun P, Baum SH, Tolias AS, Yoshor D (2012) Electrocorticography links human temporoparietal junction to visual perception. Nature Neuroscience 15(7)957-959. PubMed

Becker WJ (2020) Botulinum Toxin in the Treatment of Headache. Toxins (Basel). 12(12):803. Article

Bloss EB, Cembrowski MS, Karsh B, Colonell J, Fetter RD, Spruston N (2018) Single excitatory axons form clustered synapses onto CA1 pyramidal cell dendrites. Nat Neurosci. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0084-6. PubMed

Burette AC, Lesperance T, Crum J, Martone M, Volkmann N, Ellisman MH, Weinberg RJ (2012) Electron Tomographic Analysis of Synaptic Ultrastructure. Journal of Comparative Neurology 520(12): 2697-2711. PubMed

Burke M (2014) Why Alzheimer's drugs keep failing. Scientific American. Article

Calabresi et al., (2014) Direct and indirect pathways of basal ganglia: a critical reappraisal. Nature Neuroscience 17(8):1022-1030 Article

Chicurel ME, Harris KM (1992) Three-dimensional analysis of the structure and composition of CA3 branched dendritic spines and their synaptic relationships with mossy fiber boutons in the rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 325:169-182. PubMed

Cohen A, Burns B, Goadsby PJ (2009) High-flow oxygen for treatment of cluster headache: a randomized trial. JAMA. 302(22):2451–2457. Article

Cohen FS, Melikyan GB (2004) The energetics of membrane fusion from binding, through hemifusion, pore formation, and pore enlargement. J. Membr. Biol. 199: 1–14. PubMed

Collard & Gellman (2001) Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and prevention of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesthesiology. 94: 1133 Article

Cossell L, Iacaruso MF, Muir DR, Houlton R, Sader EN, Ko H et al. Functional organization of excitatory synaptic strength in primary visual cortex. Nature. 2015; 518(7539): 399–403. PubMed

Cragg BG (1967) The density of synapses and neurones in the motor and visual areas of the cerebral cortex. J Anat 101(Pt 4):639-654. PubMed

Dahlin E, Neely AS, Larsson A, Bäckman L, Nyberg L (2008) Transfer of learning after updating training mediated by the striatum. Science. 320(5882):1510-1512. PubMed

Dreier JP, Reiffurth C (2015) The stroke-migraine depolarization continuum. Neuron. 86(4):902–922. Article

Edelman S (2012) Six challenges to theoretical and philosophical psychology. Front Psychol. 3:219. PubMed

Escobar ML, Derrick B (2007) Long-term potentiation and depression as putative mechanisms for memory formation, in: F. Bermudez-Rattoni (Ed.), Neural Plasticity and Memory, from Genes to Brain Imaging, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Chapter 2. PubMed

Eyal G, Verhoog MB, Testa-Silva G, Deitcher Y, Benavides-Piccione R, DeFelipe J, de Kock CPJ, Mansvelder HD, Segev I (2018) Human cortical pyramidal neurons: From spines to spikes via models. Front. Cell Neurosci.12:181. PubMed

Frotscher ML, Seress L, Schwerdtfeger WK, Buhl E (1991) The mossy cells of the fascia dentata: a comparative study of their fine structure and synaptic connections in rodents and primates. J Comp Neurol. 312:145-163. PubMed

Gallistel CR, Balsam PD (2014) Time to rethink the neural mechanisms of learning and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 108:136–144. PubMed

Giraudo CG, Hu C, You D, Slovic AM, Mosharov EV, Sulzer D, Melia TJ, Rothman JE (2005) SNAREs can promote complete fusion and hemifusion as alternative outcomes. J. Cell Biol. 170, 249–260. PubMed

Govindarajan A, Kelleher RJ, Tonegawa S (2006) A clustered plasticity model of long-term memory engrams. Nat Rev Neurosci. 7(7):575-583. PubMed

Grueber WB, Sagasti A (2010) Self-avoidance and tiling: Mechanisms of dendrite and axon spacing. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 Sep;2(9):a001750. PubMed

Gustafsson B, Wigström H (1990) Long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region, its induction and early temporal development, Prog. Brain Res. 83:223–232. PubMed

Hangya B, Pi H-J, Kvitsiani D, Ranade SP, Kepecs A (2014) From circuit motifs to computations: mapping the behavioral repertoire of cortical interneurons. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 26:117–124. PubMed

Harrison SC. (2015) Viral membrane fusion. Virology 479-480:498–507. PubMed

Hebb D O (1949) (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Hernandez JM, Stein A, Behrmann E, Riedel D, Cypionka A, Farsi Z, Walla PJ, Raunser S, Jahn R (2012) Membrane fusion intermediates via directional and full assembly of the SNARE complex. Science 336(6088):1581–1584. PubMed

Hodgson SE, Harding AM, Bourke EM, Taylor DM, Greene SL (2021) A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial of intravenous chlorpromazine versus intravenous prochlorperazine for the treatment of acute migraine in adults presenting to the emergency department. Headache. 61(4):603-611. Article

Jacob AL, Weinberg RJ (2014) The organization of AMPA receptor subunits at the postsynaptic membrane. Hippocampus. 25(7):798-812. PubMed

Jahn R, Scheller RH (2006) SNAREs--engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7(9):631–643. PubMed

Janeway Jr CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ (2002) Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. 5th edition. The generation of diversit in immunoglobulins. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3642-X. PubMed

Josselyn SA, Tonegawa S (2020) Memory engrams: Recalling the past and imagining the future. Science. 367(6473):eaaw4325. PubMed

Karnani MM, Agetsuma M, Yuste R (2014) A blanket of inhibition: functional inferences from dense inhibitory connectivity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 26:96-102. Article

Kennedy MJ, Davison IG, Robinson CG, Ehlers MD (2020) Syntaxin-4 defines a domain for activity-dependent exocytosis in dendritic spines. Cell 141:524–35. PubMed

Konur S, Rabinowitz D, Fenstermaker VL, Yuste R (2003) Systematic regulation of spine sizes and densities in pyramidal neurons. J Neurobiol. 56(2):95-112. PubMed

Koyama T, Kato K, Tanaka YZ, Mikami A (2001) Anterior cingulate activity during pain-avoidance and reward tasks in monkeys. Neurosci Res. 39(4):421–430. Article

Kozlovsky Y, Efrat A, Siegel DP, Kozlov MM (2004) Stalk phase formation: effects of dehydration and saddle splay modulus. Biophys J 87(4):2508–21. PubMed

Kumar A, Rotter S, Aertsen A. Spiking activity propagation in neuronal networks: reconciling different perspectives on neural coding. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010; 11(9): 615–627. PubMed

Kung TA, Guyuron B, Cederna PS (2011) Migraine surgery: a plastic surgery solution for refractory migraine headache. Plast Reconstr Surg. 127(1):181–189. Article

Leikin SL, Kozlov MM, Chernomordik LV, Markin V, Chizmadzhev YA (1987) Membrane fusion: overcoming of the hydration barrier and local restructuring. J. Theor. Biol. 129, 411–425. PubMed

Litwin-Kumar A, Doiron B. Slow dynamics and high variability in balanced cortical networks with clustered connections. Nature Neuroscience. 2012; 15(11): 1498–1505. PubMed

Liu T, Wang T, Chapman ER, Weisshaar JC (2008) Productive hemifusion intermediates in fast vesicle fusion driven by neuronal SNAREs. Biophys J 94(4):1303–1314. PubMed

Lu W, Man H, Ju W, Trimble WS, MacDonald JF, Wang YT (2001) Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron 29(1):243–254. PubMed

Lu X, Zhang F, McNew JA, Shin YK (2005) Membrane fusion induced by neuronal SNAREs transits through hemifusion. J Biol Chem 280(34):30538–30541. PubMed

Martens S, McMahon HT (2008) Mechanisms of membrane fusion: disparate players and common principles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9(7):543–556. PubMed

Martin SJ, Grimwood PD, Morris RG (2000) Synaptic plasticity and memory: an evaluation of the hypothesis. Ann Rev Neurosci 23:649-711. PubMed

McMahon HT, Missler M, Li C, Südhof TC (1995) Complexins: cytosolic proteins that regulate SNAP receptor function. Cell 83, 111–119. PubMed

Meador et al., (2009) Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 360(16):1597-605. Article

Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, Shi J, Sabbagh M (2017) Why do trials for Alzheimer's disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 26(6):735-739. Article

Minsky M (1980) K-lines: a theory of memory. Cognitive Science 4:117–133. Article

Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, Boly M, Pickard JD, Tshibanda L, Owen AM, Laureys S (2010) Willful modulation of brain activity in disorders of consciousness. N Engl J Med. 362 (7):579-589. PubMed

Moore JJ, Ravassard PM, Ho D, Acharya L, Kees AL, Vuong C, Mehta MR (2017) Dynamics of cortical dendritic membrane potential and spikes in freely behaving rats. Science doi: 10.1126/science.aaj1497 PubMed

Moser EI, Krobert KA, Moser MB, Morris RG (1998) Impaired spatial learning after saturation of long-term potentiation. Science. 281(5385):2038-2042. PubMed

Munafò MR, Smith GD (2018) Repeating experiments is not enough. Nature 553:399. PubMed

Murayama Y, Biebetamann F, Meinecke FC, Muller KR, Augath M, Oeltermann A, Logothetis NK (2010) Relationship between neural and hemodynamic signals during spontaneous activity studied with temporal kernel CCA. Magn Reson Imaging. 28(8):1095-1103. PubMed.

Nagy AJ, Gandhi S, Bhola R, Goadsby PJ (2011) Intravenous dihydroergotamine for inpatient management of refractory primary headaches. Neurology. 77:1827–1832. Article

O'Donnell P, Grace AA (1993) Dopaminergic modulation of dye coupling between neurons in the core and shell regions of the NAc. J Neurosci 13(8): 3456-3471 Article

Oelkers M, Witt H, Halder P, Jahn R, Janshoff A (2016) SNARE-mediated membrane fusion trajectories derived from force-clamp experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(46):13051–13056. PubMed

Onn SP, Grace AA (1994) Dye coupling between rat striatal neurons recorded in vivo: compartmental organization and modulation by dopamine. J Neurophysiol 71(5): 1917-1934. Article

Palmer LM, Shai AS, Reeve JE, Anderson HL, Paulsen O, Larkum ME (2014) NMDA spikes enhance action potential generation during sensory input. Nat Neurosci 17(3):383-390. PubMed

Piorazi P, Mel BW (2001) Impact of active dendrites and structural plasticity on the memory capacity of neural tissue. Neuron 29:779-796 PubMed

Piovesan EJ, Kowacs PA, Tatsui CE, Lange MC, Ribas LC, Werneck LC (2001) Referred pain after painful stimulation of the greater occipital nerve in humans: evidence of convergence of cervical afferences on trigeminal nuclei. Cephalalgia. 21(2):107–109. Article

Popper C (1965) The logic of scientific discovery. ISBN:0-415-27843-0 Book

Rand RP, Parsegian VA (1984) Physical force considerations in model and biological membranes. Can J Biochem Cell Biol 62(8):752–759. PubMed

Robbins MS, Kuruvilla D, Blumenfeld A, Charleston L 4th, Sorrell M, Robertson CE, Grosberg BM, Bender SD, Napchan U, Ashkenazi A (2014) Trigger point injections for headache disorders: expert consensus methodology and narrative review. Headache. 54(9):1441–59. Article

Rubin DD, Fusi S (2007) Long memory lifetimes require complex synapses and limited sparseness. Front. Comput Neurosci. 1:7. PubMed

Rumpel S, LeDoux J, Zador A, Malinow R (2005) Postsynaptic receptor trafficking underlying a form of associative learning. Science 308(5718):83–88. PubMed

Saldanha IJ, Cao W, Bhuma MR, Konnyu KJ, Adam GP, Mehta S, Zullo AR, Chen KK, Roth JL, Balk EM (2021) Management of primary headaches during pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding: A systematic review. Headache. 61(1):11–43. Article

Schaub JR, Lu X, Doneske B, Shin YK, McNew JA. (2006) Hemifusion arrest by complexin is relieved by Ca2+-synaptotagmin I. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 748–750. PubMed

Schneider T, Erben U, Moos V (2017) Peripheral T-Cell Reactivity to Heat Shock Protein 70 and Its Cofactor GrpE from Tropheryma whipplei Is Reduced in Patients with Classical Whipple's Disease. PubMed

Schoenbaum G, Chiba AA, Gallagher M (1998) Orbitofrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala encode expected outcomes during learning. Nat Neurosci.1(2):155-159. PubMed

Selimbeyoglu A, Parvizi J (2010) Electrical stimulation of the human brain: perceptual and behavioural phenomena reported in the old and new literature. Front. Human Neuroscience 4: 46. PubMed

Shors TJ, Matzel LD (1997) Long-term potentiaion: What's learning got to do with it? Behavioral and brain sciences 20:597-655. PubMed

Spruston N (2008) Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(3):206-221. PubMed

Stuart GJ, Spruston N (2015) Dendritic integration: 60 years of progress. Nat Neurosci. 18(12):1713-1721. PubMed

Tonegawa S (1983) Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature 302: 575-581. Article; Review1, Review2

Tonegawa S, Pignatelli M, Roy DS, Ryan TJ (2015) Memory engram storage and retrieval. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 35:101-109. PubMed

Trotta L, Weigt K, Schinnerling K, Geelhaar-Karsch A, Oelkers G, Biagi F, Corazza GR, Allers K, Infect Immun. 85(8):e00363-17. PubMed

Tye KM, Stuber GD, de Ridder B, Bonci A, Janak PH (2008) Rapid strengthening of thalamo-amygdala synapses mediates cue-reward learning. Nature 453, 1253–1257 PubMed

Unekawa M, Tomita Y, Toriumi H, Suzuki N (2012) Suppressive effect of chronic peroral topiramate on potassium-induced cortical spreading depression in rats. Cephalalgia. 32(7):518–527. Article

Vadakkan K.I (2021a) Neurological disorders of COVID-19 can be explained in terms of both "loss and gain of function" states of a solution for the nervous system. Brain Circulation. Article

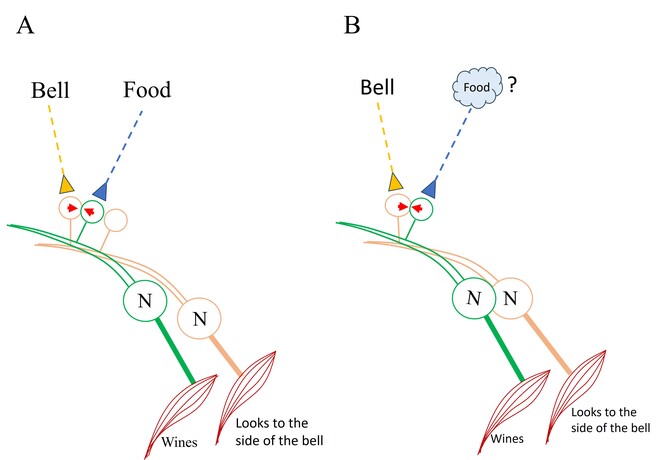

Vadakkan K.I (2021b) Framework for internal sensation of pleasure using constraints from disparate findings in nucleus accumbens. World Journal of Psychiatry. Article.

Vadakkan KI (2007) Semblance of activity at the shared post-synapses and extracellular matrices - A structure function hypothesis of memory. ISBN:978-0-5954-7002-0 Download

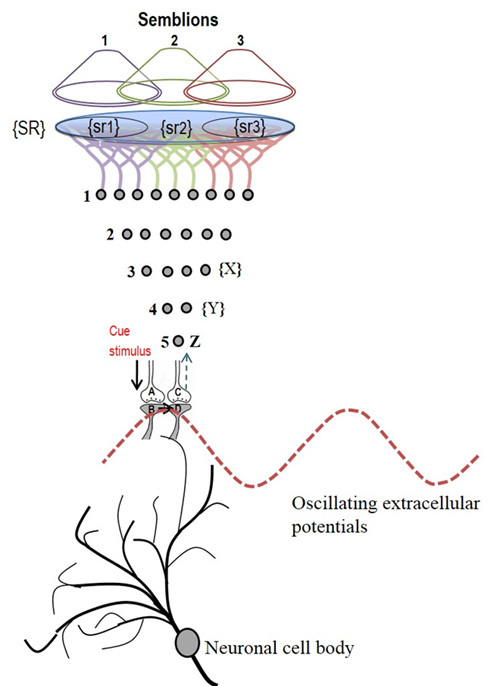

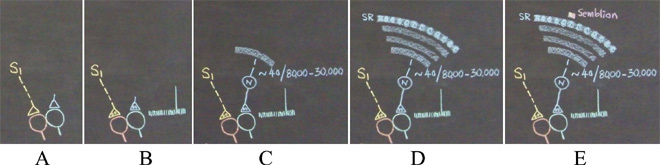

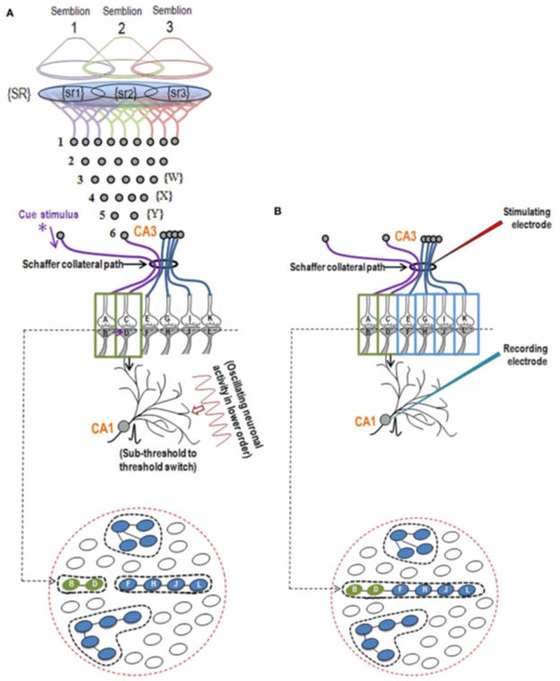

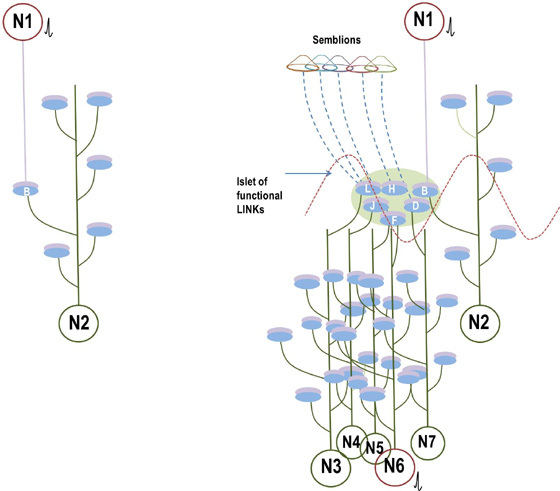

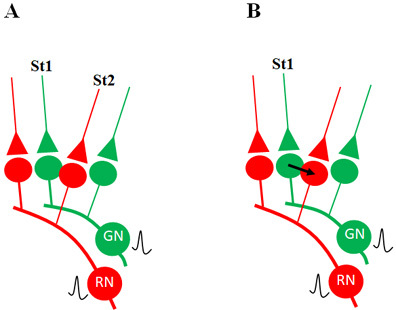

Vadakkan KI (2010) Framework of consciousness from semblance of activity at functionally LINKed postsynaptic membranes. Front Psychol. 1:168. Article

Vadakkan KI (2011) Processing semblances induced through inter-postsynaptic functional LINKs, presumed biological parallels of K-lines proposed for building artificial intelligence. Frontiers in Neuroengineering 4:8. PubMed

Vadakkan KI (2012a) The nature of "internal sensations" of higher brain functions may be derived from the design rules for artificial machines that can produce them. Journal of Biological Engineering. 5;6(1):21. PubMed

Vadakkan KI (2012b) A structure-function mechanism for schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 28;3:108. PubMed

Vadakkan KI (2012c) A structure function mechanism for schizhophrenia. Front. Psychiatry. Article

Vadakkan KI (2013) A supplementary circuit rule-set for the neuronal wiring. Front Hum Neurosci. 7:170. Article

Vadakkan KI (2015a) A framework for the first-person internal sensation of visual perception in mammals and a comparable circuitry for olfactory perception in Drosophila. Springerplus. 4:833. Article

Vadakkan KI (2015a) A pressure-reversible cellular mechanism of general anesthetics capable of altering a possible mechanism for consciousness. SpringerPlus 4:485 PubMed

Vadakkan KI (2016) The functional role of all postsynaptic potentials examined from a first-person frame of reference. Reviews in the Neurosciences (Explained how a neuronal soma is flanked by a large number of internal sensory processing units and their relationship with neuronal firing). Article

Vadakkan KI (2016b) Neurodegenerative disorders share common features of "loss of function" states of a proposed mechanism of nervous system functions. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. Article

Vadakkan KI (2016c) Rapid chain-generation of inter-postsynaptic functional LINKs can trigger seizure generation: Evidence for potential interconnections from pathology to behavior. Epilepsy & Behavior. 59: 28-41. Article

Vadakkan KI (2018) A learning mechanism completed in milliseconds and capable of transitioning to stabilizable forms can generate working, short and long-term memories - A verifiable mechanism. Peerj Preprints Article

Vadakkan KI (2019) From cells to sensations: A window to the physics of mind. Phys Life Rev. 31:44-78. PubMed

Vadakkan KI (2020) A derived mechanism of nervous system functions explains aging-related neurodegeneration as a gradual loss of an evolutionary adaptation. Curr Aging Sci. 13(2):136-152. Article

Vadakkan KI (2021c) Golgi staining of neurons: Oxidation-state dependent spread of chemical reaction identifies a testable property of the connectome. OSF Preprints

van den Heuvel MP, Sporns O. Rich-club organization of the human connectome. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011; 31(44): 15775–15786. PubMed

Vaz AP, Inati SK, Brunel N, Zaghloul KA (2019) Coupled ripple oscillations between the medial temporal lobe and neocortex retrieve human memory. Science 363:975-978. Article

Ventura R, Harris KM (1999) Three-dimensional relationships between hippocampal synapses and astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 19 (16):6897–906. PubMed

Wegener G, Rujescu D (2013) The current development of CNS drug research. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 16(7):1687-1693. PubMed

Whitlock JR, Heynen AJ, Shuler MG, Bear MF (2006) Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science. 313(5790):1093-1097. PubMed

Yagishita S, Hayashi-Takagi A, Ellis-Davies GC, Urakubo H, Ishii S, Kasai H (2014) A critical time window for dopamine actions on the structural plasticity of dendritic spines. Science. 345:1616–1620. Article

Zimmerman CA, Leib DE, Knight ZA (2017) Neural circuits underlying thirst and fluid homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 18(8):459-469. Article

Zingg B, Hintiryan H, Gou L, Song MY, Bay M, Bienkowski MS et al. Neural networks of the mouse neocortex. Cell. 2014; 156(5): 1096–1111. PubMed